This story originally published in the Peninsula Clarion.

Nikiski, an industrial base for oil, gas, mining and fishing for decades, was once rich with industry money and a number of bars, restaurants, cafes, and independent video store and even an arcade. As oil prices plummeted and a fabrication plant and fertilizer producer closed, so did many of the area’s businesses. Now, community members are working to revitalize the area.

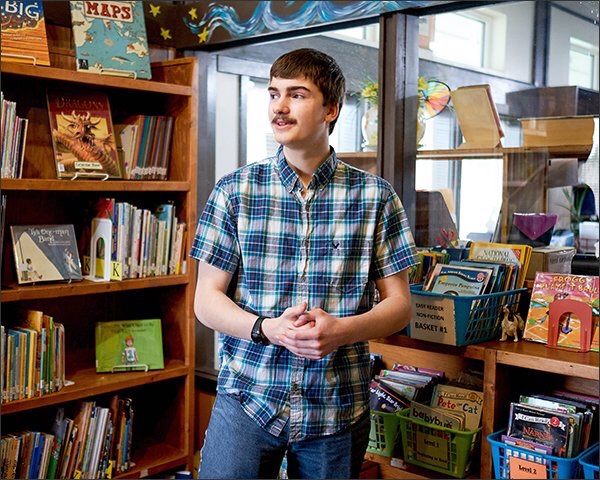

Todd Brigham grew up in Nikiski. He left for college and returned more than nine years ago with his wife to start his family. Last month, Brigham quit his job as an engineer for ConocoPhillips to give back to his hometown. Now, he said he’s working harder than he ever did as an engineer.

“We want to help our youth navigate life,” Brigham said. “The Compass is really about building relationships, and teaching practical life skills, and really getting the youth pointed in a healthy direction.”

Brigham and his wife Emily are starting the Compass, a youth center, they hope to open just in time for school to start. Currently under construction, the center will feature a lounge area, games, pool table, air hockey, foosball, computers for children to work on homework, a conference room where Brigham hopes to offer work sessions on personal finance, first aid and other practical knowledge, a shop area where kids can learn to make ceramics with the center’s donated wheels and kiln and a coffee house that community youth will help run in the morning. Brigham said the revenue made from the cafe will support the center and will be open to the public every morning.

A 1953 Willys pickup truck donated by Brigham will also offer youth an opportunity to learn about automotive restoration.

“We can paint it Compass colors and drive it in the Fourth of July parade next summer,” Brigham said.

The youth center is located next door to M &M Market, near Nikiski Middle/High School, and is geared towards children in that age range. Drop-in service will run from 2:15–3:30 p.m. on weekdays.

In the summer, Brigham hopes to offer outdoor programs where youth can go canoeing and hiking in the area.

“It’s actually surprising, a number of the youth around, even though we have it all around us, they’ve never been out,” Brigham said. “We want to get them out in creation and enjoy the rivers and the hills.”

Brigham has worked with many of the youth in Nikiski through his church, Lighthouse Community Church. He’s setting the Compass up as a faith-based organization, but the center is open to any youth in the area.

“I’ve met a lot of good kids, with a lot of ideas a lot of talent, but not a whole lot of direction,” Brigham said. “There’s a number of youth that I’ve run into or stopped by that aren’t really involved in anything and, or dropped out of school. I think we can really fill a gap where they can really have a place to belong and help some of them through the tough years of being a teenager. (Nikiski) is a place where there’s not a whole lot to do around here, (the Compass) is a place where they can come and hang out.”

Residents of Nikiski say they see a need for the Compass and more community centers, as well. Stacy Oliva, a co-vice chair of Citizens for Nikiski, Inc., a group petitioning the state to incorporate Nikiski as a city, and a member of the North Peninsula Recreation Service Area Board, said she loves the concept of the Compass.

“It’s definitely needed,” Oliva said. “It’s so needed in every community, and it’s neat they chose here.”

There were no community centers like there are now when Oliva was growing up in Nikiski in the 70s.

Both Oliva’s maternal and paternal grandparents homesteaded in Nikiski in the 1950s. She said she’s seen Nikiski change from a homestead area to a growing community.

“[Nikiski] lost its homestead feel,” Oliva said. “We always had really small family get-togethers and we relied on each other, shared things. It’s more commercialized now, and we don’t have neighborly gatherings like we used to, but now there are so many events where people are getting together here.”

She said she’s seen more families come to Nikiski in pursuit of a rural lifestyle, and a growth in agricultural enterprises, including marijuana.

“It’s still very industrial as an area, but it’s definitely very family-oriented,” Oliva said. “Nikiski is very unique and it has great families.”

While there is a growth in families, Oliva said Nikiski has also seen a growth in criminal activity, which she said is the community’s biggest drawback.

“Unfortunately, remoteness has left the door open for criminal activity, more so now than in the (Trans-Alaska Pipeline System) days,” Oliva said. “It’s just now it’s more unpredictable… You can stay under the radar here.”

Brigham is hoping to keep Nikiski’s youth out of trouble.

“We found that the youth that doesn’t have something to be part of or something to do, is getting in trouble, or are headed in a bad direction, so we really want to come alongside them and help them be set up for success,” Brigham said.

This is the first center dedicated to youth in Nikiski. The Nikiski Community Recreation Center, which was created after the Nikiski Elementary — housed in the same building — was shut down in 2004, also offers youth programs, a playground, a teen center that hosts monthly teen nights, youth sports programs and space for area-wide events.

Rachel Parra, the recreation director of the North Peninsula Recreation Service Area, said the Nikiski Community Recreation Center has been a work in progress, but that it’s central to community events. The list of programs and events is growing every year. Residents this summer can now enjoy Yoga in the Park for free at 10 a.m. on Wednesdays and next month, the Nikiski Pool is hosting its first ever cardboard and duct tape boat race.

“The primary industry out here is oil and gas and fishing, but it seems like we have a really growing desire to have a community out here and offer different things for teens to do,” Brigham said. “I know the rec center has been really trying to help get stuff like that going as well as (Challenge Martial Arts).”

Brigham said he sees a desire for community growth in Nikiski, and it’s because of a collaborative effort between the area’s organizations and businesses.

“We love Nikiski, we love being out here and we have the woods, and the ocean and a lot of things to enjoy, but we want to come together as a community of people as well,” Brigham said. “I see that happening out here as well. With oil and gas and fishing, it’s very seasonal. It ebbs and flows with oil prices, so we get little booms and slow periods. It seems right now we are headed in a new direction and I’m excited.”

The strip mall where M &M Market and the Compass are housed, has gradually added businesses in the past few years — what was once a nearly empty strip mall is now home to two restaurants, a martial arts studio, a ceramics shop and now the Compass youth center. Felix Martinez, owner of M &M Market, feels the ebbs and flows of Nikiski economy strongly. Last year, the hardware store closed and a community gas station stopped offering repairs, after which Martinez said his sales dropped between 12–14 percent.

“Our little community economy imploded last year,” Martinez said. “Though, Nikiski has been up and down since the beginning.”

Martinez has been an owner at M &M Market since 2003, but the store has been around since the 60s. He said in order for business to grow in Nikiski, people need to be willing to take risks.

“I don’t think I’ve seen someone take as big a chance as (Brigham),” Martinez said. “It almost brings a tear to my eye. When you see someone take a chance it makes you smile and you remember there are good people in the world. Our youth is our future, and if Todd next door is putting this much into our youth, it’s the least we could do to support him.”

The Compass is preparing to have an open house on Aug. 11 where the community can come and learn about the center’s goals.